October 2025

|

| On the day of my dad's wake, |

| I found this gravestone to a |

| 18th century Hugh Woodbury! |

The purpose of this post is to talk about what my dad was to me. He wasn't a perfect guy. I never felt an instinct to worship him (though since his death, I've been tempted based on the number of staff members in his assisted living community who spoke to me positively about him: he was never rude; he never made unreasonable demands; he was always upbeat and pleasant...).

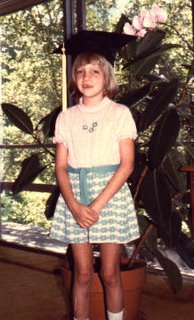

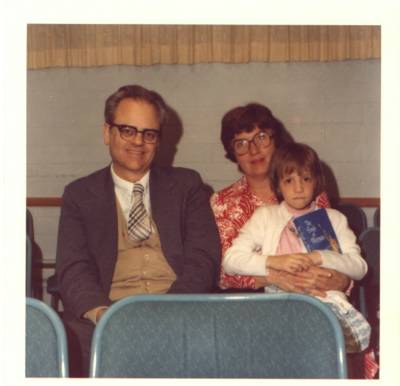

When I was younger, I performed with him in plays. On church camping trips, I recited poems with him, including Lewis Carroll's "You are Old, Father William." I played the trumpet in high school because my dad played the trumpet when he was younger. Regarding school, he occasionally helped me with my math homework.

My parents and I both moved (separately) to Maine in 1996. They lived on Peaks Island but came to the mainland for church on Sundays. Every Sunday until COVID lock downs, we ate lunch together, usually sandwiches prepared by my mom.

Eventually, my parents left Peaks Island for a series of retirement homes. I began to accompany my dad to his doctors' appointments as his "scribe." Starting approximately four years ago, after my mother moved into Memory Care, I began to see my dad twice a week: once after I visited my mom and once when I picked him up for church. Every Sunday, I would pull up to the facility and watch a very thin, stooping man with (usually) uncut white wild hair--yet immaculately dressed in a suit with tie and maroon sweater--slowly make his way out of the building to my car.

2025 saw a radical change. After a stint in rehab, he did not return to physical church though we continued to attend on Zoom. I also began to eat Sunday breakfasts with him. I would order blueberry pancakes and Eggs Benedict, then split the meals between us. About this time--and to my eternal gratitude--hospice took over much of his care.

2025 saw a radical change. After a stint in rehab, he did not return to physical church though we continued to attend on Zoom. I also began to eat Sunday breakfasts with him. I would order blueberry pancakes and Eggs Benedict, then split the meals between us. About this time--and to my eternal gratitude--hospice took over much of his care.

In May, it seemed that the final days were close. However, as hospice told me in wonder, "Your parents are a surprise!" My dad kept going. His long-term memory was mostly gone (though occasionally he would remember information I'd passed on to him about my job), but he continued to read books I brought him, to watch the cars and trees outside his windows, to now and again check the news on his home computer, to take whirlpool baths, to spend time with my mom (staff and hospice would arrange for them to sit together), to watch Zoom church, including (marvels of technology!) our old ward in Schenectady, New York, and to treat all visitors with great friendliness.

At the end of every visit, as I was leaving, he would say, "Say, 'Hello' to your cats!"

At some point on this blog, I will comment on my relationship with my mother. It was more complicated than my relationship with my father--and what I got out of the two relationships, in terms of positives, was quite different.

From my father, I got a lack of judgment. It wasn't only that he refrained from lecturing me: telling me what I should do better--pronouncing how much he loved me in the same breath as asking me why I wasn't leading a completely different life--scolding me for not performing certain actions...

| |

| Pastel by my mom of my dad with | |

| my sister's cat. |

When I made my visits, I was simply Kate, his youngest. I was me; he was Dad. I never had to wonder if he would be happier if I was someone else. Although a romantic and an idealist, he had the touching and remarkable ability to accept what was before him. Life is life.

I will miss him very much.

And, Dad, my cats are doing well.

***

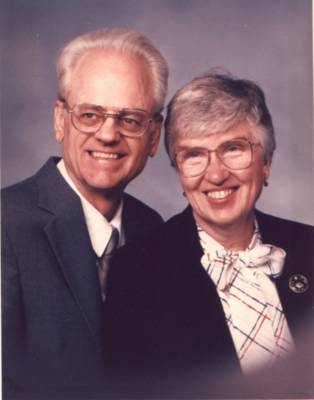

June 2005

My parents are, on paper at least, opposites. My mother is an artist with a B.A. in Art from Brigham Young University and a M.A. in Printmaking from SUNY Albany. She taught for several years before her first child was born. Like everyone in our family, she reads a lot, especially mysteries and currently Forester's Horatio Hornblower series.

My parents are, on paper at least, opposites. My mother is an artist with a B.A. in Art from Brigham Young University and a M.A. in Printmaking from SUNY Albany. She taught for several years before her first child was born. Like everyone in our family, she reads a lot, especially mysteries and currently Forester's Horatio Hornblower series.

She also reads history, and is something of an amateur historian on a few subjects; when I taught seminary for our church, she was my go-to person for The New Testament. My mother read to me up until I was in Junior High, and she probably would have kept going if I hadn't turned into a teenager and persisted in finishing the books we started. These days we share a love of books on tape.

|

| My father labeled this image |

| "Joyce out-standing in her garden." |

My mom used to invent stories as well, mostly about a troll named Milo. Her considerable artistic talents are more visual (she understands abstract art!), and in the last ten years that creative flair has expressed itself more and more in her flower garden(s).

My father is a scientist with a Ph.D. in nuclear physics. He worked at G.E. Research & Development all his career and was part of the team that recreated the first industrial diamond. He claims not to understand Quantum Mechanics, which is kind of like Shakespeare disclaiming higher education (it may be true, but come on, it's Shakespeare). My clearest childhood memory of my father is of him paraphrasing science articles at the dinner table. Even now, he will pass on tidbits from Greene's Elegant Universe or articles he has read, and he helps me considerably with my sci-fi stories. Despite being the introvert in the relationship, my father has acted in a number of plays and once recited Lewis Carroll's The Song of the White Knight with me playing the part of Alice. Nowadays, he plays the stock market, levels the lawn (and levels the lawn...and levels the lawn). He also has a penchant for history and when I taught seminary, he was my go-to person for Old Testament and Book of Mormon.

So, on paper, my parents would seem to be opposites, complementary opposites, but opposites nonetheless. Extrovert/Introvert. Science/Art. Language/Math. However, these are false dichotomies. My parents operate, as the saying goes, on the same wavelength. One component of that wavelength is their service in the Mormon Church (in which we were all reared). They work in the Boston Temple every week which, for people living in Maine, entails a fair amount of time and money, all volunteered.

Another component, and the one that brings us back to popular culture, is their commonsense. They are commonsensical. Not given to sentimentality (although a romantic streak runs through the family) but people who have a high level of discernment. There's not any cynicism involved. They just see the world as is and keep going. (Maybe it's a gardening thing.) Which isn't to say my parents, like all of us, don't have their pet peeves, their soap boxes and their sacred cows but they also, to a remarkable degree, try to look at themselves objectively. I'm not saying they always succeed. Does anyone? But the point is, they try.

What this character analysis boils down to is: they did not raise their children to be relativists. Life might all be some mind game, God might be a boiled egg and time might not exist, but if you're an artist and a scientist of my parents' schools of thought, you start from the proposition that something is going on around you, you are collecting and reacting to data. Sure, it could all be in your head, but that's a totally boring approach to life so why bother going there? Start with the proposition that some sort of reality does exist, that we are all experiencing some degree of synchronicity and then accept the hard work of trying to understand it (which hard work should not entail either angsty self-righteous intellectualism or undisciplined "oh nobody knows anything anyway" gloopiness) and, well, life rapidly gets very fun.

Which is what my parents taught me and is what I'd like to thank them for here. Life is great! Life is fun! My parents are kind of like spiritual anti-Augustinians. The body is good! The physical world is a blessing! It's swell to be alive! Isn't it interesting? Isn't it grand? They are Mormons born and bred (and I am deliberately using the "older" term since pioneers thrived in both my parents' ancestries), and their particular attitude towards life is influenced by the progressive positivism implicit in Mormonism: that life matters, that it isn't just some way-station where we hang out and mope until God snatches us home; it isn't simply an experiment where God prods us with a few trials and notes our responses and pats us on the head.

Which is what my parents taught me and is what I'd like to thank them for here. Life is great! Life is fun! My parents are kind of like spiritual anti-Augustinians. The body is good! The physical world is a blessing! It's swell to be alive! Isn't it interesting? Isn't it grand? They are Mormons born and bred (and I am deliberately using the "older" term since pioneers thrived in both my parents' ancestries), and their particular attitude towards life is influenced by the progressive positivism implicit in Mormonism: that life matters, that it isn't just some way-station where we hang out and mope until God snatches us home; it isn't simply an experiment where God prods us with a few trials and notes our responses and pats us on the head.

Life is worth living for its own sake because only living life (for its own sake) can prepare you for the next stage. Life should fully engage us. God wants it to. You can't live in heaven if you don’t know how to live on earth. Come Judgment Day, God will hand out as much freedom and experience and love as we can handle. If we can't, if we settle for dry, stale ideologies, if we weigh ourselves down with distrust, anger, guilt and cynicism, that's the kind of heaven we'll settle for.

So, in a way, the relativists are right, because the heaven you think is possible is the heaven you will get. The point of religion, Mormonism in particular, is to train us not to settle for less. And it starts with our immediate surroundings.

Okay, morphed a bit there into my own opinion, but it all goes back to my parents. I grew up knowing that my parents had a multiplicity of interests that went beyond their family and for that matter, each other. Those interests often dovetail (like the lawn, the dirt, the vegetable garden, the flower garden and the fruit trees: ALL related) in their theological beliefs as well as the arts, but my parents were always individuals in my eyes, which, for a child, can be revelatory if a little frightening. These people, one learns fairly early, are not just here for my benefit. And too, I grew up seeing that, contrary to an attitude I've run into lately, religious observance does not limit a person to a bland-room-with-bland-curtains-and-bland-floor mentality.

Now, my parents have never been into The Top 40. They don't particularly like action movies (Schwarzenegger variety). They detest commercials. They have never, to my knowledge, attended a rock concert. And we grew up without a TV (well, for most of the time). You couldn't have paid my mom to watch soaps. Which isn't to say we didn't go out to see movies (where my father, the most honest man alive, would let us sneak food into the theaters). Still I mostly grew up going to ballet and listening to opera and classical music and seeing Shakespeare. My parents truly enjoy doing those things. But—here's where the commonsense comes into play—it was never "we're seeing this because of how important it is"; rather, "we're seeing this because we like it." They also like Agatha Christie (my mom), Alice in Wonderland (my dad), Peter, Paul & Mary, Garrison Keillor (before he got popular, mostly), chocolate (my mom!), Tolkien, shaggy dog stories (my dad) and so on and so forth.

It never seems to occur to them that it's fun! That's it's funny! You don't have to believe that watching action movies involves a deliberate suspension of belief to which all parties are privy (the secret compact theory of popular culture); you just have to believe that people like doing it.

So, Mom and Dad, thanks for teaching me that life is fun, that enjoying life is as much a part of religion as praying or reading the scriptures, that the world is a fantastic place that it never harms us to find out more about and especially for loving life and each other.